By MARTHA NAKAGAWA, Rafu Contributor

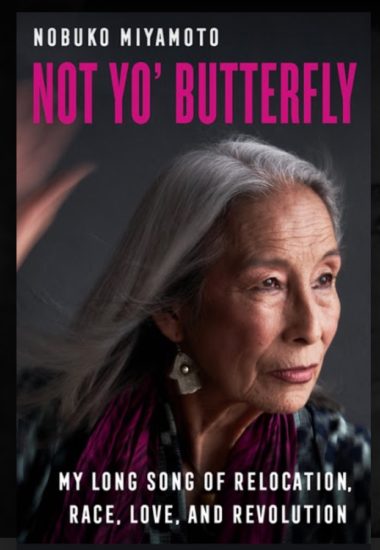

Playful, provocative, never boring — that sums up Nobuko Miyamoto and her memoir, “Not Yo’ Butterfly: My Long Song of Relocation, Race, Love and Revolution,” published this year, following the release of a new album, “120,000 Stories.”

Nobuko Miyamoto speaks at civil rights activist Yuri Kochiyama’s memorial program in 2014 in Little Tokyo. In “Not Yo’ Butterfly,” Miyamoto recounts meeting Kochiyama for the first time. (MARIO GERSHOM REYES/Rafu Shimpo)

The memoir starts with a bang and takes off into a poetic whirlwind. Miyamoto certainly had an extraordinary life.

From a young age, Miyamoto showed promise as a dancer, winning a scholarship to the American School of Dance in Hollywood, and would be mentored by such dance legends as Jerome Robbins and Jack Cole.

At the age of 15, Miyamoto was cast in the movie “The King and I,” starring Yul Brynner. Miyamoto’s behind-the-scenes recollections are fascinating as she writes about such incidents as dancing on a smooth, black floor that started to melt under their bare feet due to the hot klieg lights.

At the age of 15, Miyamoto was cast in the movie “The King and I,” starring Yul Brynner. Miyamoto’s behind-the-scenes recollections are fascinating as she writes about such incidents as dancing on a smooth, black floor that started to melt under their bare feet due to the hot klieg lights.

She then went on to attain every dancer’s dream of performing on Broadway when she landed a role in the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical “Flower Drum Song.” However, it was during this production that she started to question what she was actually doing, especially during one number when she faced the audience and sang, “chop suey, chop suey.” But this was the late 1950s. Yellowface and racist stereotypes were the norm.

Miyamoto turned down the opportunity to continue performing in the “Flower Drum Song” in London and returned to Los Angeles, where she auditioned for the “West Side Story.” She beat out hundreds of other dancers to become one of two Asian Americans on the movie set. (The other was Jose De Vega, who was of Chinese, Pilipino and Guatemalan descent.)

Meanwhile, as Miyamoto was coming of age, the U.S. was embroiled in the Vietnam War and the Civil Rights Movement.

Miyamoto hooked up with a filmmaker who wanted to do a documentary on the Black Panthers. This changed Miyamoto’s career path.

When Miyamoto returned to New York, she was no longer the aspiring dancer willing to please White America, but became a community activist who discovered her voice as an Asian American.

Miyamoto’s New York years are riveting as she writes about the Young Lords, Asian Americans for Action (often referred to as Triple A), Warriors of the Rainbow and the Basement Workshop.

She gives a wonderful description of her first meeting with the legendary activist Yuri Kochiyama and explains how New York Asian Americans became associated with Malcolm X’s phrase “Chickens come home to roost.”

Most importantly, readers will learn how Miyamoto partnered with Chris Iijima and later with Charlie Chin to record the seminal album “A Grain of Sand,” which is considered the first Asian American folk album.

She also shares how she almost walked off the set of a national TV program,“The Mike Douglas Show,” which she and Chris Iijima had been invited to sing on by Yoko Ono and John Lennon, who were co-hosting the show with Douglas for a week.

After touring the country, Miyamoto resettled in Los Angeles where she gave birth to a Japanese/African American boy at a time when racially mixed children were a rarity within the Nikkei community.

Senshin Buddhist Temple and Rev. Mas Kodani loom large in her life. We learn that it was Rev. Kodani who had challenged Miyamoto to write her first Obon song. We also learn how Great Leap, the nonprofit arts organization that Miyamoto still heads, was created.

But some details are lost in the creative writing. The beginning is a bit confusing since the story jumps around, and the reader is never told what year Miyamoto is born, although it becomes clear she was born before World War II. It would also have been nice to know whether Miyamoto was delivered by an osanba-san (midwife), which was common at the time or was born at the historic Japanese Hospital in Boyle Heights.

Readers must also assume that Miyamoto grew up somewhere in Southern California, on Kingsley Street, which she mentions, but Kingsley Street is a long avenue that cuts through Los Angeles. We get oriented when she later points out East Hollywood.

One glaring mistake is a reference to a Nikkei gang as the Black Wands. This should be Black Juans. They were a postwar Eastside gang, headed by the notorious General (aka Jim Matsuoka).

The spelling of Japanese words should also be double-checked. For example, a go- between should be baishakunin, not bishakunin; older sister, nesan, not neisan; the beginning of the Buddhist chant as namu amida butsu; and unsure whether the word ore in the memoir is referring to orei, which is an expression of gratitude.

There is also reference to the Hawaiian word, kotonk, which the memoir refers to as “empty as bamboo,” but ask any Hawaiian Japanese and they will say it is the sound of an empty coconut.

Another common error that should be corrected is the reference to the 442nd Regimental Combat Team as the “most decorated infantry unit of the war.” The 442nd was the most decorated unit in U.S. military history for its size and length of service.

World War II camp terminology should also reconsidered. United States citizens cannot technically be “interned” in “internment camps” since internment connotes the legal incarceration of enemy aliens. Two-thirds of Japanese Americans imprisoned in the War Relocation Authority camps were U.S. citizens, which the U.S. government euphemistically referred to as “non-aliens.”

The memoir also states that at the Santa Anita detention center “Japanese farmers made gardens with their smuggled seeds.” Numerous former WRA inmates have stated that this occurred at the permanent WRA camps, and while it’s possible that this may have also happened at the temporary detention centers, a citation may be necessary.

Despite these shortcomings, the memoir captures an important part of American history that, at this point, has been rarely written about, especially by someone who lived it. This is well worth reading. Then, take time to listen to the “120,000 Stories” album.

Saturday, June 26 – Book Launch Celebration

3 p.m. Pacific

Free. RSVP: https://notyobutterfly.eventbrite.com

Co-sponsored by Eastwind Books of Berkeley; J-Sei; Asian American Diaspora Studies at UC Berkeley

University of California Press

$85 hardback

$29.92 paperback

$29.95 ebook

344 pp

"book" - Google News

June 06, 2021 at 06:13AM

https://ift.tt/3fVc9og

BOOK REVIEW: Chronicle of an Extraordinary Life - The Rafu Shimpo

"book" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2Yv0xQn

https://ift.tt/2zJxCxA

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "BOOK REVIEW: Chronicle of an Extraordinary Life - The Rafu Shimpo"

Post a Comment