I have always loved the writing part of my scientific career, but had never seen a path to develop it. Beyond putting out research papers in my field of immunology, I never had time to think about a larger piece of work. The cycle of grants and papers didn’t leave much room for anything else. Little did I know that, at the start of last year, this was going to change: I was about to find myself writing a book about a pandemic, during the pandemic, while working as a medical researcher investigating the pandemic.

I’d not intended to write a book on infectious diseases, but my laboratory’s closure in March 2020 left me needing something to do, other than home-schooling my children and worrying about my lack of new experimental data. Luckily, I had a plan B. In November 2019, I had been in touch with a literary agent, Caroline Hardman at Hardman & Swainson, and pitched her a book about my life in science — after all, I’d written already for online periodicals and started a blog, which seemed to be generally well-received. Not entirely surprisingly, she said ‘no’, because a book about my career would be of interest solely to me and maybe some members of my family. Caroline gave me a much better idea: writing a book about the science behind infectious disease. Then, six months later, fate intervened in the form of the COVID-19 pandemic — giving me both time to write by shutting my lab, and thematic motivation on the subject matter.

Getting an agent came through a number of factors; many are the same as those required for a scientific career. Persistence: I had been trying to pitch my careers book for 12 months before I spoke to Caroline. Networking — I was fortunate that Caroline also represents Dan Davis, an immunologist at the University of Manchester, UK, who has written three books and served as an informal writing mentor to me. And some serendipity: the pandemic meant that infections, the topic I was best placed to write about, was of wide interest.

As my agent, Caroline helped me to develop the overall pitch for the book, getting it into a shape that would be looked at by the editors at publishing houses. Pitching a non-fiction book is not dissimilar to crafting a grant submission. You write an abstract of the whole work and a brief outline of the plan, and include some preliminary data (in the form of previous written work and a sample chapter), a short CV, a comparison with the rest of the field and something resembling an impact statement (a summary of who might actually buy this book and why). After I completed these steps, Caroline shopped the manuscript around to various publishers. This part of the process was definitely familiar from trying (and failing) to get manuscripts into journals; the best part was that I didn’t have to do it myself.

The pitch was accepted by Sam Carter, editorial director at Oneworld Publications, in May 2020, and my first draft’s due date was set at December the same year. Oneworld is an independent publisher with a focus on non-fiction and has published two Booker prizewinners. In their science list, I am in extremely good company; both the Nobel prizewinner Barry Marshall and the former president of the Royal Society Venki Ramakrishnan have published books with them.

But a pitch is not the same as a completed book; up until May 2020, the process hadn’t been especially demanding of my time. It had required the odd hour here and there, but that didn’t really prepare me for what was next. Oneworld gave me a target of 90,000 words, which seemed a lot, even with my experience of working on theses and lengthy papers in academia. I did some quick calculations: I needed to write around 3,000 words per week, every week, between May and December.

Thus commenced a mad dash against the clock. In an attempt to motivate myself, I used Excel to record words written versus words required. Some weeks, I’d be ahead of the curve; many weeks, I was behind it. My mood on a Sunday evening was directly linked to how many words I’d got down on paper the week before. From May to December, Saturday and Sunday mornings would find me in front of the laptop. One of the unexpected side effects was that I found myself unable to read any other books: I just had too many words in my head already. But, curiously, having that structure and a forced deadline was in some ways beneficial; there was no time to get bored.

I owe a great debt to my wife, who, on top of her own job, took on the extra burden of childcare on these weekend mornings. Finally, late one night in December, it was done — or at least the first draft was. There were still multiple edits (and re-edits) to make, comma splices to unsplice, and proofs and print drafts to be read over the next 9 months.

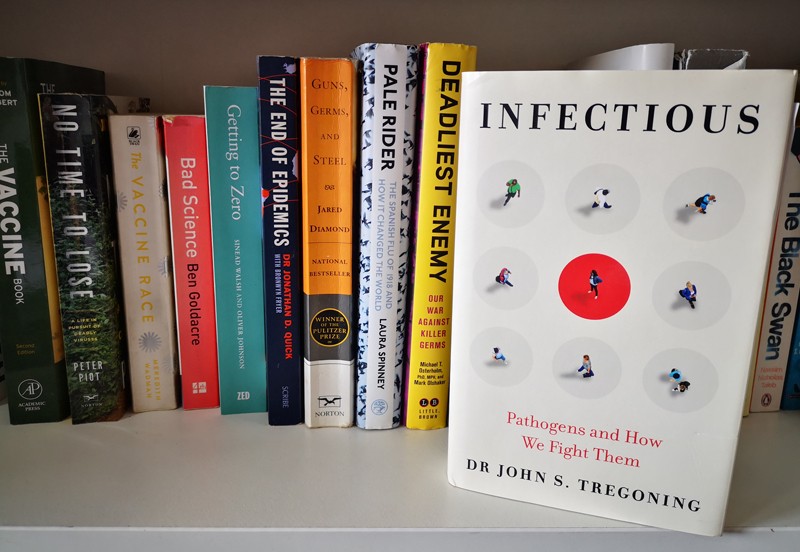

The book itself is an overview of all aspects of infectious disease. It starts with the underpinning the ‘ologies — epidemiology, microbiology, immunology — that help us to understand infectious diseases, and then moves to the drugs and vaccines that we use to prevent and cure infections. It draws a lot on the subject matter that I have been teaching for the past ten years, and I have filled it with as many facts, anecdotes and curiosities as I could find. With the help of my teenage son as my proofreader, I have tried to aim it at an audience aged 13 years and older.

So, what have I learnt?

1. Writing a book takes a lot of time. If you want to write one, be sure you have the time, as well as the space and the support to do it. It took me the best part of 12 hours per week for 30 weeks, the equivalent of about 10 working weeks. This was on top of my day job and the unbridled joy of home-schooling. Some might say this was quite quick, but it certainly required a lot of extra effort.

2. Build a portfolio. None of this happened from a standing start. Building a portfolio of writing was crucial. Evidence that I could string a sentence together that others were prepared to read was essential in getting the process moving. It doesn’t all have to happen at once; I started writing when I was 19. If it is a path you are interested in, set up your own blog and speak to editors about writing for them. It is equally important to develop a voice — which comes from time and experience.

3. Writing a book is really hard. There is a persistent myth that everyone has one book in them, in the same way that nearly everyone has an appendix. But getting either out is not a simple matter. The process of writing took a lot of time and drained a lot of my creative energy.

4. Learn the craft. Although reading widely is important, there are also technical aspects to writing. My shelves are weighed down with books about writing. From the creative side of the process (Stephen King’s On Writing) to the technical (Roy Peter Clark’s Writing Tools). Writing well pays off in other areas: papers and grants are often best presented as stories, for example.

5. Read widely. Read whatever you can: magazines, journals, high-brow literature, tweeny dystopia. All have value in terms of pacing, words and structures that you can draw on. They also give you a wellspring of facts to make use of.

6. Word dump. ‘Pantsing’, in which you just throw the words on the page in a rough order and worry about shaping them later, can be an immensely helpful way to start writing. Hemingway described this process as ‘write drunk, edit sober’. The way the creative bit of my brain works is different from the critical part, and they don’t work well together — which is true for most people. It applies to all writing — theses, papers, applications. Get the words out there, then worry about whether they make sense later.

7. Persist. The book I wanted to write about my fabulous life in science was rejected multiple times (as was my children’s book about an octopus who only laughs after he gets ten-tickles #spoiler) before the preliminary conversation that led to an entirely different book. As with all things in science, persisting does eventually pay off, but you need to develop a thick skin.

8. Road test your writing. Get feedback on what you have written before. Some of this can come in the form of downloads, likes and the general machinery of social media. But you do also need direct input. One sure-fire test is whether someone (such as a magazine editor) will pay for it.

9. Love words. Play word games, make puns, thrash your children at Scrabble: it all helps to refine the key tool of the trade.

10. Bank it. Collect snippets of random information wherever you can. I had a wealth of random statistics about infectious disease that added ‘colour’ to my book. Did you know that the longest tapeworm ever found in a human was 24 metres long?

As the book finally reaches physical publication on 14 October 2021, I ask myself: was it worth it? I have no idea how it will affect my career. In terms of the grants and papers, it might not change that much.

However, it will, I hope, open up opportunities for science communication and engagement through festivals and talks, which might then open up other unanticipated opportunities. It also gave much-needed structure to my pandemic year, and writing a book is one of the things I have always wanted to do — and I really enjoyed it. So, on balance, yes it has been worth it. But, ultimately, judge for yourself: Infectious is out now.

"book" - Google News

October 15, 2021 at 09:35PM

https://ift.tt/3BKmewM

How I wrote a pop-science book - Nature.com

"book" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2Yv0xQn

https://ift.tt/2zJxCxA

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "How I wrote a pop-science book - Nature.com"

Post a Comment