This summer brings a bumper crop of great reads, from fiction to memoir, graphic novels to translations — including new books from Akwaeke Emezi, Rivka Galchen, Paula Hawkins, Brandon Taylor, and more. You just made it through one of the hardest, weirdest winters on record. Don’t you deserve a little pleasure?

Set in a vibrantly conjured Central Florida, Arnett’s second novel concerns itself with the frustrations and disappointments of family life both big and small, calling attention to the thin membrane that separates control and chaos, love and violence. The story follows Sammie, a fiercely unhappy woman who works from home and cares for her young son, Samson, while her wife pursues a career as a successful lawyer. From the outset, Samson is a difficult, unknowable child who throws temper tantrums and breaks things — and as he gets older, his hostility toward Sammie only deepens, eventually pushing her over the edge. It can be hard to escape the belief that other peoples’ lives are better, more fulfilling, and more organized than our own. There is something refreshing, even comforting, about this story, a complicated portrait of parenthood in all its unruly beauty. —Cornelia Channing

“I am going to survive prison. I am going to create a beautiful life for myself … Ashley, your father is coming home.” When Ashley C. Ford receives this letter from her father, she doesn’t know how to feel: Her father has been in prison for the majority of her life, and now that he is being released, she must face the fact that she and her parent are complete strangers to each other. Vivid and vulnerable, the effortless dialogue and beautifully woven narratives throughout Somebody’s Daughter makes the memoir read almost like fiction. Ford takes us through her life — from her childhood in Indiana to her experience as a writer in New York City — and explores how she became the woman she is today, both because of and in spite of her family. —Mary Retta

Flyn, an investigative journalist from Scotland, is fascinated by ecosystems that have been torched and then deserted by humans. We’re talking the Chernobyl exclusion area, a buffer zone in Cyprus, a chain of land in France still riddled with unexploded ordnance from World War I, and other sites considered “wrecked” — and that are now, in their own ways, recovering. Flyn roams across these accidental experiments in rewilding and reports back on what she finds amid the rubble. —Molly Young

Translated from Portuguese by Zoë Perry

When was the last time you found yourself sitting among a group of people you’d never met before? After more than a year of the pandemic it might be hard to pin down the moment, but you may remember how you felt — eddies of language whirling around you, conversational shorthand, inside jokes, and obscure references never quite settling into a narrative you could understand. That’s how I felt reading Sevastopol by Brazilian writer Emilio Fraia: I opened the book and found myself in a story that had seemingly started without me. Based loosely on Leo Tolstoy’s story suite The Sevastopol Sketches, Fraia’s book offers up three glancingly linked stories. In the first, a young woman tells an elliptical tale about her mountain-climbing obsession; in the second, a man disappears while staying at a dilapidated countryside inn; and in the third, a young playwright collaborates with an older theater director to produce a play about a Russian painter and the Crimean city of Sevastopol. Translated from the Portuguese by Zoe Perry, these tales don’t operate the way most tales do; they adhere to their own separate sense of languid time. —Tope Folarin

When editorial assistant Nella Rogers smells cocoa butter on her floor at work, she’s immediately thrilled: Her diversity campaigning has finally paid off, and Wagner Books has hired Hazel, another Black woman. But when mysterious notes begin to appear on Nella’s desk — “LEAVE WAGNER. NOW” — suddenly everyone in the office, including Hazel, becomes a potential foe. A former publishing employee herself, Zakiya Dalila Harris has taken her own experiences in a notoriously white field and created a debut novel that is the perfect mix of social commentary and fast-paced thriller. Poignant, daring, and darkly funny, The Other Black Girl will have you stressed and exhilarated in equal measure through the very last twist. —Mary Retta

When I crack open Future Feeling, I’m a little worried its contents will spill out into my life and zip around, ripping little holes in the space-time continuum. That’s how much wildness Lake has packed into less than 300 pages. There are hexes and holograms, characters called Witch and Stoner-Hacker, a pet goose, “Butt-meters,” and an “Unfuneral.” It’s set in an alternate 21st-century New York, a place that Pynchon and Ballard might have dreamed up on a psilocybin retreat in the desert. Underpinning Future Feeling is a wry refusal to try to convince us of anything; it resists the primary rule of narrative, that everything must be believable to be believed. This is a taste of what it means for a novel to give zero fucks. —Hillary Kelly

After the success of her debut novel, Red, White & Blue, Casey McQuiston is back with another romance that deftly captures the frustrations and fears of falling in love. This one follows August, a college loner whose years spent obsessively investigating a family member’s disappearance with her mom have made her more comfortable with facts than friends. Shortly after moving to New York, August meets Jane, the punk-rock girl of her dreams, on the Q train. She soon discovers that her new crush is an unintentional time traveler stuck on that subway line and struggling to recall her past. Electric chemistry and ’70s music are crucial to unraveling the mystery, so expect plenty of kissing (“for research”) and song references, as McQuiston uses Jane’s memories to weave in an homage to the radical history of early queer activists. One Last Stop is an earnest reminder that home — whether that means a time, a place, or a person — is worth fighting for. —Jennifer Zhan

In this collection of raw, emotional, and raunchy stories, Ojeda showcases the power (and in some instances, the lack thereof) that surrounds a community of queens and legends trying to make it in New York City. The characters are trans and queer Latinx people trying to win, thrive, and meet a few men along the way, embracing their sexuality to the fullest. “Mirror, mirror on the wall, who’s the sluttiest New York loca of them all?” asks Deborah Hilton, a queen who competes in trans beauty pageants and praises God for giving her “plenty of beauty and plenty of dick.” Sometimes, though, they’re just trying to survive, struggling with addiction and facing violence from police and the inhumanity of society. Above all, Las Biuty Queens — which also includes an introduction by Pedro Almodóvar — is about resilience and the importance of community. —Wolfgang Ruth

Translated from Spanish by Katherine Silver

It’s rare for a novel that’s assigned as part of high-school curricula to remain a cult literary item decades after it was published. In Mexico, 1981’s Battles in the Desert, by the celebrated novelist José Emilio Pacheco, is one of the exceptions — and now it’s been treated to a fresh translation, on the occasion of its 40th anniversary. Told from the perspective of an adolescent boy in the wake of World War II, it’s a story of forbidden love set against the backdrop of Mexico City’s rapidly changing Roma neighborhood, then a working-class enclave with a tight social fabric. (It’s now one of the world’s most fashionable zip codes.) Pacheco captures the early rumblings of the city’s transformation into a global metropolis, when Mickey Mouse and Coca-Cola ushered in a new age of American-style materialism. This upheaval parallels the protagonist’s own loss of innocence, as he experiences the agony of unrequited desire for his best friend’s mother. At only 71 pages, plus a new postscript by one of Mexico’s “It” writers of the moment, Fernanda Melchor, Battles is an unpretentious beach read with style and substance. —Max Pearl

The organizing principle of this collection is a familiar one: A group of gifted artists who toiled in relative obscurity for years — largely because gatekeepers could not or refused to recognize their talent — finally receive their due. In this case, the artists are Black cartoonists who published their work in Chicago’s vibrant Black press throughout much of the 20th century. Featuring a cover by Kerry James Marshall and essays by Ronald Wimberly and Charles Johnson (who, in addition to being a National Book Award–winning novelist, was also a pioneering cartoonist), this book is an extension of an exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago that will open in June entitled Chicago Comics: 1960 to Now. The comics in this book are fantastic: innovative, incisive, layered, and — most importantly—blazingly funny. They also point to another organizing principle of this book: Though many of these artists were ignored by the mainstream, they created their own mainstream, a thriving space in which their Blackness was a starting point for rigorous engagement with American society. —Tope Folarin

Since its appearance four years ago in Grindr’s now-defunct digital magazine, INTO, JP Brammer’s beloved advice column “Hola Papi” has been known for its humorous and down-to-earth approach to dealing with love, heartbreak, and identity. (It’s now syndicated on the Cut.) In Brammer’s first book, he borrows his column’s name and format to tell personal stories of coming out in a WalMart parking lot, reckoning with his Mexican-American identity while working at a tortilla factory, and forgiving his homophobic middle-school bully after encountering him on a gay dating app. Through essays that blend memoir with solicited advice, he addresses the messy emotions and experiences that follow us from adolescence into adulthood: How do we let go of childhood trauma? How do we grow confident in our identities? Brammer responds through his own deeply personal stories, while gently reminding us that he doesn’t have all the answers. No one does. —Miguel Salazar

In the next year, Akwaeke Emezi will release their first memoir, Dear Senthuran, their first poetry collection, and their first romance novel. These come on the heels of The Death of Vivek Oji in 2020 and Freshwater in 2018, two astonishing, original novels that revealed 33-year-old Emezi as a literary wunderkind, capable of finger-snap transformations on the page. (They also published a YA novel called Pet in 2019.) Dear Senthuran is structured as a collection of letters to friends and family, about reading sex-advice columns as a child and the transformative power of gender-affirming surgery, the rampant jealousy inside their MFA cohort and the burnt bodies on the roadside in their hometown of Aba, Nigeria. Each letter is fiery and diamond-hard, written by a once-in-a-generation voice. —Hillary Kelly

I want to bottle up the hilarious and infuriating energy of Everyone Knows Your Mother Is a Witch and offer it to the creators of the paltry, meager little things that pass for novels these days: This is how you do it! Galchen steps back in time to 1615, to the town of Leonberg, Germany, where crotchety Katharina Kepler is accused of witchcraft by jealous neighbors. The novel itself is framed as an “account,” dictated by illiterate Katharina to her literate neighbor and friend, of the six years of investigation and suspicion that dog her after one accusation grows into a chorus. Not only does Galchen create in Katharina one of the wryest and funniest voices I’ve heard in a long time, she also manages to write a brilliant treatise on the inflation of a small lie into a huge one, and the merry-go-round of accusations that have plagued women since Eve (allegedly) took a bite out of that apple. —Hillary Kelly

Translated from Japanese by Lucy North

A novel about a real-life voyeur seems appropriate in the age of social media, where opportunities to monitor one’s frenemies and exes proliferate like hydrangeas in summer. The stalker of this novel, a woman who works as a cleaner at a hotel, performs her surveillance in broad daylight, tracking the movements of a seemingly random woman who lives a totally unremarkable life. Why the obsession, then? Buried inside that question is the mystery of this deadpan novel by one of Japan’s most lauded young writers. —Molly Young

There are two things Joan knows about herself: She is depraved, and she’s a survivor. In Animal, Taddeo’s first novel, the gripping, first-person narrative depicts the slow burn of a woman simultaneously discovering herself and falling apart. After witnessing her partner commit a horrific act of violence, Joan flees New York City in search of an old friend she hopes can help her recover. Instead, she ends up coming face-to-face with her traumatic past. In Animal, Taddeo digs into the same themes she explored in her critically acclaimed nonfiction work Three Women — the thrills and horror of feminine desire — while debuting an impressive skill for fiction. Animal is a viscerally satisfying depiction of female rage and a gripping exploration of what it’s like to endure male violence that is both mundane and life-altering. —Mary Retta

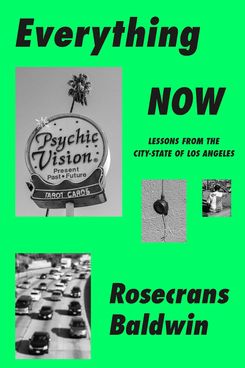

“To attempt to say what is Los Angeles, other than ‘by itself,’ sometimes feels like trying to pin down a cloud,” writes Baldwin. And yet, the novelist (You Lost Me There) manages to define, and, perhaps, redefine, the most undefinable of cities with a fresh and sometimes startling inquisitiveness. Ambitious in a way that seems to mirror L.A.’s sprawl, the story is told through a series of vignettes, combining deft on-the-ground reporting, hazy personal memories, and snippets of overheard conversations that read, appropriately, like film scripts. The territory is familiar — cults and celebrities, oil and water, disasters natural and engineered — yet Baldwin, who shares a first name with a distant ancestor for whom the city’s Rosecrans Boulevard is named, supplements his own attempts at grasping L.A. with interrogations of some of its most legendary interrogators, including Octavia Butler, Héctor Tobar, Joan Didion, and Mike Davis. Like Davis, Baldwin peels back the faded myths of stereotypes and boosterism in his effort to source the origins of L.A.’s power. But particularly when framed through last summer’s urgent demands of racial justice, it’s clear just how much L.A.’s deepening inequality threatens to tear it all asunder. —Alissa Walker

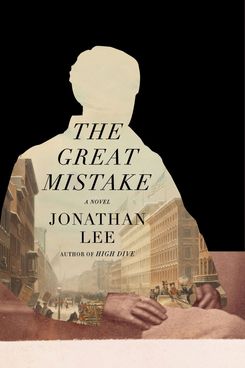

New York is back, baby! Just in time for our more liberated summer, Jonathan Lee has written a historical novel, set in turn-of-the-century Manhattan, involving ludicrously rich people and a shooting in broad daylight, that of Andrew Haswell Green, the city planner and man-about-town responsible for Central Park, the Met, and the New York Public Library. On November 13, 1903, he was returning to his Park Avenue home for lunch when a man jumped out of the bushes and shot him five times. Lee’s 2015 novel High Dive established him as a brilliant weaver of multi-thread historical narratives, and The Great Mistake promises more than a whodunnit and Edwardian tea gowns. Bring this one to Morningside Park (another Haswell project) and revel in New York, past and present. —Hillary Kelly

Translated from Spanish by Julia Sanches

When this collection of essays was first published in Mexico in 2016, it won Oliver, an emerging Mexican writer, a national award for young essayists and brought her work to readers throughout Latin America. The book is a wispy and meditative travelogue of sorts that traverses memory and place. Writing with a palpable curiosity, Oliver explores the ancient underground cities of Cappadocia in Turkey, Christa Wolf’s writings in East Germany before the fall of the Berlin Wall, and the U.S.-sponsored Cuban child exodus in the early 1960s known as Operation Peter Pan. At just 136 pages, it’s a bite-sized read, but the reflections from its ten essays will linger long after they are finished. —Miguel Salazar

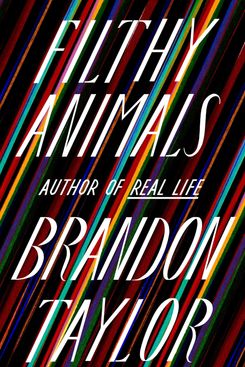

In case you’re wondering, as I was, whether the title of Taylor’s first short-story collection is a reference to that line from Angels With Filthy Souls, the movie Macaulay Culkin watches in Home Alone, well, yes, it is. (“Keep the change, ya filthy animal.”) But for all their pop-culture savvy, these 11 stories are resonant and poignant, built of long ropes of connective tissue. Filthy Animals tracks young women in love, young men itching for violence, and families shifting and twisting into different shapes. Taylor writes about relationships like a modern E. M. Forster, poking and prodding at the places where the connection is thinnest, and observing what happens when people madly attempt to shore it up. —Hillary Kelly

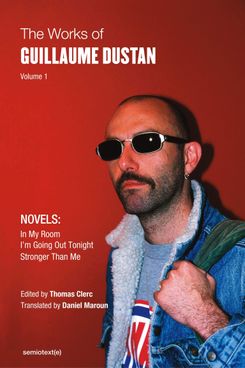

Translated from French by Daniel Maroun

As hot girl summer rolls in with the pandemic still raging — after a year at once strangely disembodying and all about the body — Guillaume Dustan’s carnal writings about cruising and drugs in 1990s Paris jolt the system. This collection of his landmark autofiction is the first time that the late Dustan, a French administrative judge by day, until he turned to writing full time, and hedonist by night, has been published in English. In this translation by Daniel Maroun, Dustan’s explicit treatments of sex and the ruthlessness of desire bring to mind Kathy Acker. Before his death from an overdose in 2005, the writer was embroiled in a widely publicized conflict with ACT UP Paris over his espousal of barebacking; adults can only be expected to care for themselves, he argued, and his stories display a similar siloing of the self, portraying sex as the main conduit to others. The novels collected here are set in a Paris where the AIDS crisis may have crested, but the virus still proliferated, including in the narrator. A constant sense of the body’s vulnerability underlies the excess: Even if a common cold could kill them, the still-living in these books keep dancing, keep desiring, at the knife’s edge of risk. —Kira Josefsson

Translated from French by Alison L. Strayer

Yasmina Reza, a French novelist and playwright, has centered much of her work on the buttoned-up crises of the middle class. Her most recent book, Anne-Marie the Beauty (in Alison L. Strayer’s translation), dips into the fickle glamour of life onstage. Anne-Marie is an aging, lonely actress who worries she might be losing her marbles. In a richly layered monologue, she looks back on her life, starting with her childhood dreams of the theater, which never resulted in more than middling fame — and the contrasting success of her luxuriant friend Giselle, who did reach the stars, despite, or perhaps thanks to, her fabulous languor. Reza, herself an erstwhile actor, has said that she realized early on that acting “was a life of waiting and dependence” that offered little control over one’s destiny, and Anne-Marie’s life is a testament to this peripatetic existence. “What’s a person looking for, going from bar to bar like that?,” Anne-Marie asks as she recalls her youth. This novel reminds us that dreams are sometimes more precious than the real thing. —Kira Josefsson

Short stories don’t usually hold my attention — I like to know I’ll be immersed in something for 200 pages or more. But Sestanovich’s debut collection reminds me of the soulful stories that emerged in mid-century America, the heyday for the form. Each one is bursting with small, explosive moments, like fireworks illuminating the bareness of the protagonists’ lives. In “Annunciation,” a woman sitting in the middle seat on a plane watches as the couple sitting on either side of her pass a positive pregnancy test across her lap; when she tells her mother about them later, “She does not call them her friends, and this feels like losing something.” Another character thinks, “To become truly happy … is to betray the unhappy person you used to be.” Sestanovich is a skilled craftswoman, each sentence a carefully positioned tile in a mosaic. —Hillary Kelly

Most histories of American abstraction begin in the 1930s with artists like Jackson Pollock or Alexander Calder. This sumptuous coffee-table book presents a parallel timeline of modernist painting based not in the coastal cities, but in the Southwest. Founded in New Mexico in the wake of the Great Depression, the Transcendental Painting Group’s members had a distinctly more spiritual practice than their New York counterparts, producing luminous fields of organic shapes, derived from nature, the cosmos, and the subconscious. Painters such as Agnes Pelton (whose profile was elevated by a Whitney show last year) subscribed to a grab bag of mystical and pseudoscientific theories, an inclination that critics often wrote off as kitsch. Now that nondenominational spirituality is once again in the Zeitgeist, the world may be ready to recognize this distinctly American art movement and the cultural undercurrent it represented. —Max Pearl

Translated from Chinese by Jeremy Tiang

The fictional city of Yong’an is full of strange beasts, writes Yan Ge in this novel, “some identical to human beings, some truly monstrous.” Some of the beasts are heartsick, some of them joyous; some of them like breakfast cereal and others hate math. If this sounds whimsical, it is, but Strange Beasts of China goes deeper, becoming a sort of combined detective story and zoological inquiry into the nature of these beasts and the sometimes-sinister relations between them and humans. Originally published in China ten years ago, when Yan Ge was just 21 — it was, somehow, already her fifth book — it is finally out in Jeremy Tiang’s pitch-perfect English translation. The narrator, a novelist who abandoned her scholarly study of beasts for a career in letters, returns her gaze to the mesmerizing creatures when her editor commissions a story about them — “They’re a hot topic right now.” But this time, the cold distance of the lab is missing, and she’s repeatedly warned to abandon the project by her former professor, who reluctantly aids her. Yan Ge has called Invisible Cities one of her favorite books, and there are certainly affinities between these stories and Calvino’s masterpiece. A page-turner whose dense, fantastical atmosphere lingers long after the read. —Kira Josefsson

It’s been a long, lonely year of isolation and sweatpants and you deserve a fairy-tale trip to Hollywood. Love yourself and pick up this witty, glitzy novel, about the unexpected connection between an actor and an ad exec, from a member of modern rom-com royalty. With her flirty characters and sunny California setting, Guillory creates a world that makes you want to put on your fanciest outfit. —Tara Abell

In her first book, 2017’s Imagine Wanting Only This, writer and illustrator Radtke explored the disintegration of her family in a stirring, formally inventive graphic memoir. She revisits the form in Seek You, this time for a meditation on loneliness — arguably the dominant condition of modern life. The illustrations are muted, delicately rendered images of people cloistered in apartments or wandering through empty urban landscapes. In one, fingers peek warily out from behind a drawn window blind. In another, a man sits on the toilet, his pants around his ankles, staring listlessly at something, presumably a phone, that he holds in his hands. Radtke is unsentimental yet sincere, citing research on the impact of social isolation on life expectancy (it’s not good) and offering as salient a description of loneliness as I’ve read: “It’s a variance that rests between the relationships you have and the relationships you want. Loneliness lives in the gap.” —Cornelia Channing

Calling all Rachel Cuskheads and W.G. Sebald stans! Kitamura is a novelist of enchanting imagination and minimalist prose style whose new novel takes place in the Hague, where her protagonist works as an interpreter at the International Court of Justice. The novel’s plot twists are of the subtle, jaw-tightening variety rather than the dramatic, stomach-knotting sort, but it’s still fair to call it a “psychological thriller.” Intimacies is for those who like their addictive novels to sneak up behind them rather than slap them in the face. —Molly Young

To answer your first question, yes, this book about quarantine was, indeed, mostly written in quarantine. Though Manaugh (author of A Burglar’s Guide to the City) and Twilley (co-host of the podcast Gastropod) started their research long before COVID-19 hit, Until Proven Safe provides a clarifying take on recent events within the historical context of the barriers, bubbles, and bunkers that humans erect around ourselves as we wait to see “what is revealed.” As unapologetically delightful as a story about nation-eradicating fatal pathogens can be, Manaugh and Twilley travel from the site of the medieval-era hospitals anchored off the coast of Venice to keep the bubonic plague at bay, to the 2019 dress rehearsals for a then-hypothetical novel coronavirus pandemic, held in a ballroom of the Pierre Hotel on New York’s Upper West Side. As we prepare to unmask, there is perhaps no more reassuring summer read than learning how the science of isolation is consistently recalibrated to safeguard society, offering protection from biological, technological, and, yes, even extraterrestrial threats. —Alissa Walker

No one explores the twists of female relationships like crime writer Megan Abbott. This time she trades the schemes of best friends for the secrets of sisters, dancers Dara and Marie, and the one broken dude they carry with them — Dara’s husband, who was their mother’s favorite student. Set inside the cutthroat world of an upper-crust ballet school, it’s like Flowers in the Attic but with pointe shoes. —Tara Abell

Kleeman’s second novel is an eco-thriller of sorts. The story follows protagonist Patrick Hamlin, a writer who goes to L.A. to, he believes, supervise the making of his book into a film — a glamorous vision that is sorely (and hilariously) upended when, upon arrival, he discovers he will actually be a production assistant, tasked with running errands and chauffeuring a troubled starlet across a menacing California landscape. The world of the novel is an only mildly exaggerated version of our own, plagued by privatization, corporate conspiracy, and wildfires, where all but the wealthiest Californians have to drink WAT-R, a synthetic substitute for water. The novel’s central mystery simmers quietly in the background for most of the story, feeling a bit like Don DeLillo meets Inherent Vice. Throughout, Kleeman writes expressively about place and the manifold ways our lives are shaped by our imperiled environment, foregrounding the slow-motion catastrophe of climate change and its attendant anxieties. —Cornelia Channing

A love story of the most fevered, brutal order. Arezu, an Iranian American teenager, travels to Spain to meet her estranged father. Instead, she finds Omar, a 40-year-old Lebanese man with whom she begins a disorienting affair. Two decades later, Arezu returns with a friend, determined to make sense of what happened to her. Against the dramatic, punishing landscape of Andalucia, the two women open old wounds — both political and personal — and trace the connections between displacement and desire. The prose is propulsive, erotic, and darkly dreamlike, recalling the early novels of Marguerite Duras. Driven by Arezu’s longing for answers, it interrogates the narratives we assign to the past and asks what we are allowed to expect of those who love us. —Cornelia Channing

In an interview with Ebony in 1987, poet Rita Dove acknowledged that she resists taking on grandiose subjects: “I prefer to explore the most intimate moments, the smaller, crystallized details we all hinge our lives on.” In her new collection, Dove’s first volume of new poems in 12 years, she dives into tiny crevices of the world — the internal monologue of an elevator operator, an octogenarian’s exuberant mambo, the mordant humor of a philosophizing cricket — and attends to them with extraordinary care. These poems witness and celebrate the grandeur and tragedy contained in a single life, a single moment, a single word. —Cornelia Channing

Translated from Norwegian by B. L. Crook

When the author of this memoir meets people he knew in childhood, they often express surprise at the fact that he is still alive. Grue, a Norwegian academic, was diagnosed with spinal muscular atrophy at age 3, and his book — which doubles as a work of literary criticism and cultural history — is, yes, an elegant meditation on what it’s like to be a body that does not resemble most other bodies, but it’s also about aging, parenthood, memory, academia, and love. A tart and spare palate cleanser tucked into the feast of summer beach reads. —Molly Young

Levy, a British novelist, playwright, and poet, has already written two of what she calls “living autobiographies” — meaning ones written in midlife — and I see no reason why she should stop. Both Things I Don’t Want to Know (2013) and The Cost of Living (2018) were intimate and essayistic, more like highly controlled diary entries made public for our edification. The last in the trilogy, Real Estate, is plumper, venturing into ever-alluring territory: women writers and the physical spaces that facilitate their craft. Levy chronicles her own late-in-life moves and adventures to Paris and India, London and New York, and questions how writers settle in or wander about in search of the right space and a feeling of belonging. If Virginia Woolf laid the foundation for a female artist’s basic needs — a room of one’s own and enough money to keep it — Real Estate breaks the idea open. —Hillary Kelly

After a man is murdered on a houseboat in London, we meet three suspects, all women with axes to grind and something to hide. Their stories begin to bleed into each other as Hawkins navigates their private motivations and public aggressions, with her signature heightened suspense and (fun twist) some killer side-eye at the publishing industry. —Tara Abell

"book" - Google News

May 25, 2021 at 10:00PM

https://ift.tt/3wuUbOM

35 Books We Can’t Wait to Read This Summer - Vulture

"book" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2Yv0xQn

https://ift.tt/2zJxCxA

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "35 Books We Can’t Wait to Read This Summer - Vulture"

Post a Comment